Growing up in Laguna Beach, California, Larry Stewart was always focused on sports. Football, basketball, surfing — he excelled at it all. But the artist inside was always there.

“I was always doodling in my notes,” he said. “And they looked beautiful, but I probably didn’t read back over the actual notes.”

He went to college at Lindsey Wilson University in Kentucky to play baseball. He studied graphic design and also took some studio art classes, and that is when he really fell in love with painting.

“I look back to stuff I was doing in college, and at the time I thought it was freaking Picasso,” he said with a laugh. “I thought they were amazing. And now, I see them today, and it is kind of hilarious.”

Whenever he and his teammates got a break from baseball, they would go to Nashville to stay with one of his teammates’ mothers, who lived outside the city.

“I’m a huge surfer, but at the time I thought that might be the one city I could live in that doesn’t have a beach,” he said.

Still, after school, he moved to Hawaii for a few years, then back to Laguna when COVID hit. That is when he really threw himself into his art.

“I was bartending for about a year, and then I had a couple posts on Instagram kind of go viral,” he said. “I quit bartending and dove headfirst into being a full-time artist. And the first year or two was a little stressful, but now that I have been pretty consistent at it, I’m starting to learn the business a little more. It’s been great.”

Stewart’s father, Lance, also lived a double life as an athlete and an artist. He earned his fine arts degree from Cal Berkeley, where he also played football.

“Usually the two don’t really mix, but in our case, it did,” Stewart said.

When he began to really express interest in art, his father built a studio in the backyard for him, and it inspired his father to get back into art more, too.

“Painting was his first love, and he was really talented, but he never made enough money, so he didn’t have the time to do it,” Stewart said. “But when I started studying it, he made time to do it too. And then we eventually did a whole series of works together, about a hundred of them.”

After that, his father was picked up by a gallery, and Stewart started doing collaboration shows with him back in Laguna. Lance would also come to visit Larry in Nashville to work in his studio together.

He would come out here all the time the first year I moved here, and we would just paint for the week and bust out five or 10 paintings,” he said.

The third time Lance was visiting, the two of them were in the studio, and Larry could tell his father wasn’t feeling well. He tried to minimize how bad he was feeling, but after much protestation, Larry got him to the hospital, where they learned the medicine he had been on to treat his diabetes for the past three years was not meant to be long-term.

“His kidneys were killing him,” Stewart said. “He had a massive heart attack and was on life support for a couple of days, but then he passed away.”

The final painting, the father and son were working on at the time, hangs high in Stewart’s studio, where he said it feels like his father is always with him.

“It is my favorite painting we ever did together,” he said.

Despite the tragedy, Stewart did not stay out of the studio long. In fact, it was one place where he could still feel his dad with him.

“It was the place I wanted to be most. It’s where I feel like I’m with him,” he said. “It was a little tough to try and paint the style that we did together because it was totally separate from what I do on my own. But I’ve done a couple since then — I can’t let it ruin my life. Painting is what I do and what I love. I am going to make it motivate me to be more successful and make better art.”

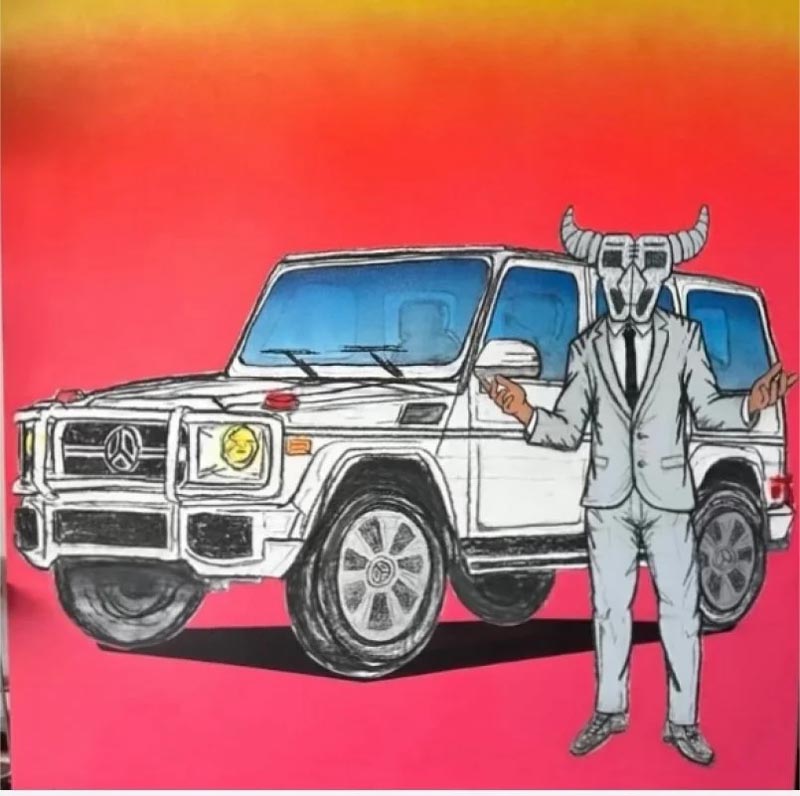

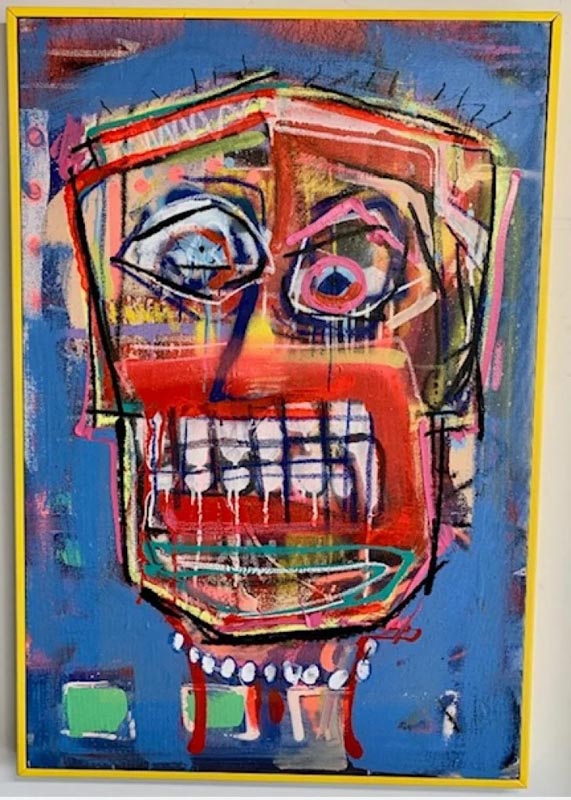

His natural talent has evolved in style and technique, and really, his understanding of how to use the materials correctly has developed through trial and error. It has also evolved because Stewart gets antsy working in the same style for too long.

“In the studio I can do something for about two weeks, and just hyper focus and become obsessed with it, and then I have to go to the next thing, and then the next thing, and then the next one,” he said. “So I have many different styles that I’ve generated over the last few years.”

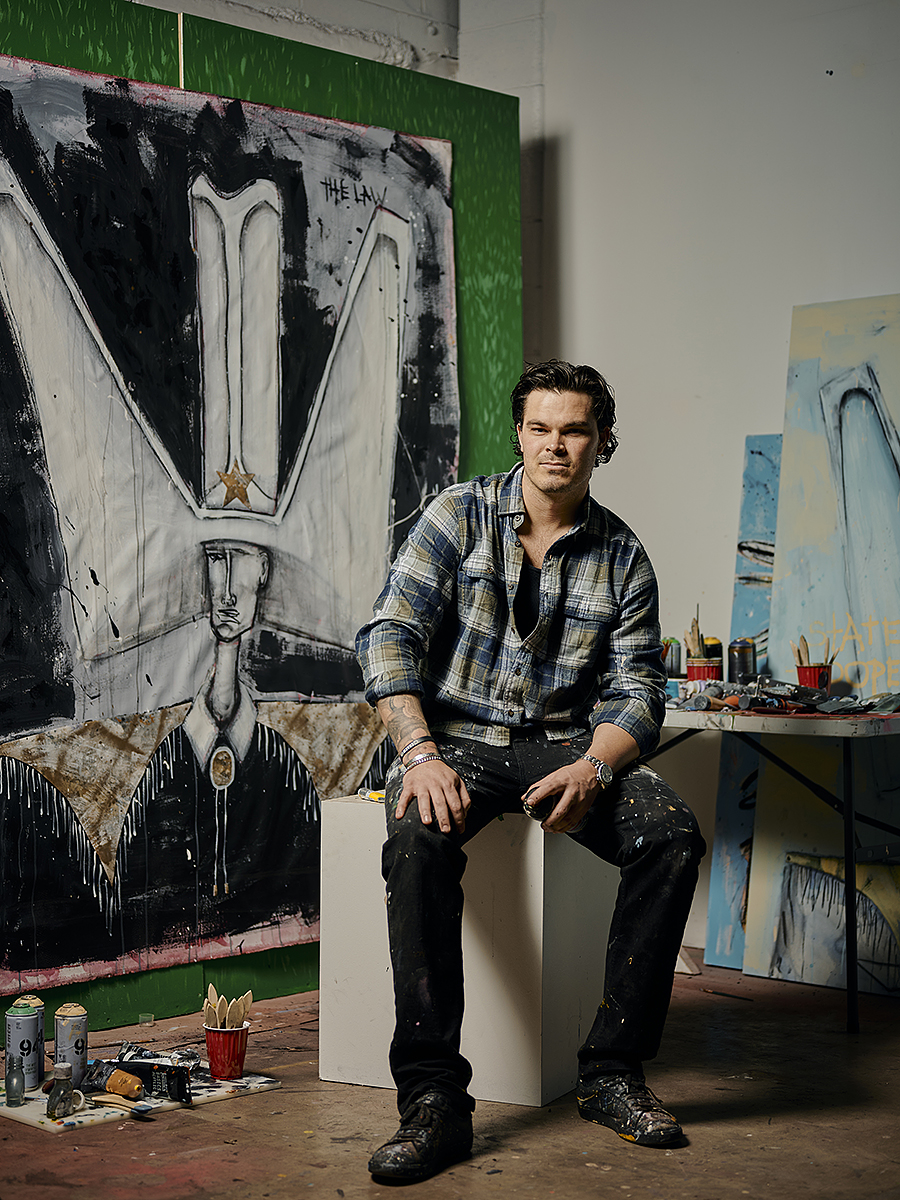

Stewart’s current studio space is in The Forge, an artist and maker space in the railyard district, where he continues to evolve, currently leaning into Southern and Western influences.

“Once I moved out here, I could see a huge shift in my art,” he said. “A lot of my work is large-scale, so it’s a statement piece. It’s nice when the statement piece lends itself to conversation at a party or family gathering.”

Stewart likes to team up with a nonprofit at each of his shows. At his most recent solo show at V.A.L. Gallery, he sold a handful of tickets for a private whiskey tasting, with the proceeds going to Mechanics on a Mission, which provides reliable transportation to Middle Tennessee families in need.

“I get most of my ideas and inspiration right before I go to bed,” he said. “And also, just … everywhere. Sometimes I’ll be walking down the street and see a cool-looking puddle and think about how I can try and recreate that. Or I get inspiration from social media or TV, or cartoons. Really, everywhere.” He keeps a running thread on his phone saved as ‘million dollar painting ideas.’

Naturally outgoing, Stewart has no problem spending time with potential collectors or talking about his art in a way that gets them excited to share his story too. He loves what he does, and it’s clear to everyone he interacts with. Especially his daughter Stetson, 1, who is with him in the studio every day.

“She’s the one who gives first approval,” he said. “If I see a smile on her face, I know it’s a good one. If I don’t, we’re gonna switch it a little bit.”