When you lift an instrument made by Charles Horner you sense the perfect balance of wood and air. It’s as if the key raw material isn’t the wood, but what is absent, some longing. From nearly nothing, from something others would throw on a fire—a rough-hewn core of a fallen tree—Charles Horner makes music.

Charles Gene Horner, 83

Rockwood, TN. Charles Gene Horner hands me a fiddle, one that I recognize has taken him more than one hundred hours to perfect. He wants me to touch it, feel the armor of ten coats of varnish, what has taken an entire dry autumn to complete. Holding it, I no longer need his permission and find myself running my hand along the curves, noting the hand-carved fern scroll.

There’s an inlay that outlines the instrument as delicate as an embroidery stitch. He reads my next question from my gesture of following that thread, and offers a near field guide to this artifact. This fiddle is nearly a plant, nearly wild, nearly endangered. He recalls the American holly and walnut inlay he chose for the embellishment of this particular species.

The tuning pegs are made of Brazilian rosewood cut back in the 1940s. Now, the fiddle has become something more, an exotic, a graft, a hybrid, with a story that extends to the Amazon rainforest and carries with it a grandfathered in contraband. Rosewood is found in remote locations, more remote than Rockwood, Tenn., and is deemed criminal to chop or import since 1991. Charles assures me he has records that show this wood dates from a harvest many decades ago. I assure him that I can’t think of any finer way to honor a tree’s life more than this exquisite art object.

Shyly, I bring the fiddle close to my face, where I can smell it, and allow my chin a moment’s intimacy on the rest. My desire to hear it played well is palpable. I hand the fiddle back to Charles and he reaches into some old rugged case for a bow, and sets it down across the strings. Music fills the maker space.

Charles Horner, now 83, is Tennessee’s elder luthier and makes fiddles and mandolins, and on occasion, a banjo. He’s been ‘at this work’ since he was about 14. The list of musicians who have made the pilgrimage to his remote mountain home, some many times, includes the likes of Earl Scruggs, Bill Monroe, Jimmy Martin, Curly Fox, John Hartman, Mel Tillis, Fletcher Bright, and Kenny Sears, fiddler player for the Time Jumpers. “There’s no telling how many recordings my violins are on,” said Charles.

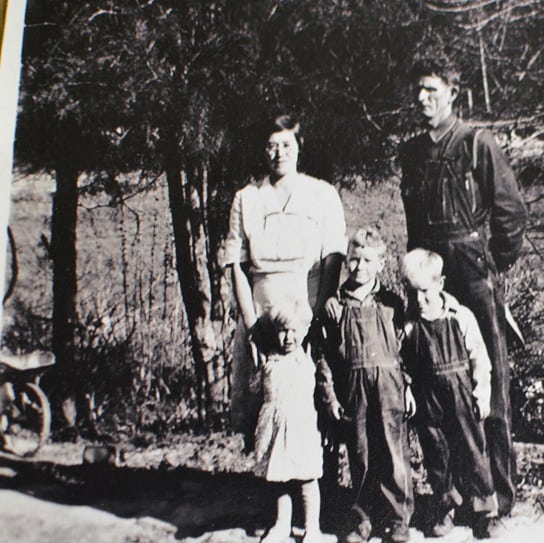

Charles Horner, third child from the left, with his family on the mountain in the early 1940s

Beyond the workshop, across a pond, sits a one-room log cabin where he was born in 1933. His father, Bruce Horner, was also born in that cabin in 1903. “My great-great grandfather served in the Revolutionary War, I’m told, and settled this land. Most people wanted to live in the valleys where the soil was rich. But here on the mountain it was a rather isolated place.” Except for his service in the U.S. Navy, Charles Horner has always been at home on this mountain.

Anne Horner, his wife, invites me to take a walk around the pond, through the muggy heat of August, the tall grass. We walk a gravel path toward the cabin, both of us hoping to work out some stiffness. In her voice I hear the admiration she has for her husband, as she points out the repairs he’s made to their rural life. Their love has been kept between them for 59 years like a cedar chest with mitered corners, and all sharp edges sanded and softened. I also hear in her voice the refrain about poor health and getting older. They are survivors these two, like the cabin. She’s been through cancer and its harsh treatment, and he has lost a foot to an amputation, and has a prosthetic that only slows him down a bit.

Anne Horner shows me her garden and stops to picks tomatoes just outside the workshop.

This walk with Anne Horner is not a detour to the story I am seeking, but takes me up the steps and into the heart of where Charles Horner’s story begins. Anne and I climb the board ramp up to the cabin porch where wagon wheels lean amidst a tangle of vines. There’s a wooden barrel, a chair. We step inside the cabin made from straight poplar logs and Anne said she can’t imagine how anyone raised large families in a place so small. One small window stares back at us. We both shake our heads and welcome a return to the expansive outdoors, the hills, and a stand of tall Joe-pye weed full of the hinges of yellow swallowtail butterflies.

Back at the workshop, Charles takes up the story where we left it. “My brothers and I slept upstairs in the loft of that old cabin.” He gestures out the window. “Up in that loft was an old trunk and in that trunk, my granddaddy kept an old German violin.” Where it came from is a bit of a mystery and lost in the telling, though he has a photo of his father playing it, or perhaps posing with it for the camera. It may have come from a jewelry store in Rockwood, Tenn.

The first violin Charles saw as a boy was this German instrument that was kept in a cedar chest in the loft of the cabin. He and his brother banged it about and when Charles mastered his luthier skills and had the proper tools, he repaired the face of the violin. Today, this inspiration piece is pristine.

“Oh, I thought it was the most beautiful thing in the world, and I still have it,” he said. Charles motions that he wants to show me the catalyst for this career of his and steps over to remove a dry towel spread across an old fiddle case. He uses these towels all around the room to keep the dust out. There’s nothing pretentious about this workshop where every space is used to stack curly maple boards or line up clamps like stair step children along the peg board above the workbench. He clicks the latches, just as he did the old trunk in the cabin loft as a child. There, fitted into the faded fabric, is a red fiddle that gleams.

Charles’ uncle is seated and his father plays the old German violin Charles would discover in the cabin loft, and find his life’s calling

“I learned to make fiddles so that I could properly repair this one,” he said. “My brothers and I had banged this one up pretty bad and it never had a case until I bought this one for it.” The violin looks pristine. Charles tells me he made it a new top in 1984. He was already a master, back then.

Charles Horner’s craftsmanship has earned him a Tennessee’s Governor’s Award. His instruments are documented by the Smithsonian and have toured with the Southern Arts Federation and numerous museums. He says the early violins he made were crude as he struggled with techniques and began acquiring a proper set of tools, and some he had to make himself or make do.

Charles has made a cello, a double bass, violas, more than 60 mandolins, but more than 500 violins. The violins are the most satisfying, he admits, though mandolins ebb and flow in popularity from time to time. A Charles Horner mandolin is coveted because they are rare.

“I’m basically self-taught,” said Charles. “You can work it out by yourself, but it’s not easy. There are schools now where you can learn some aspects quicker, but you still have to work at it to become good. I guess it was around 1948 when I started; I was just 15 years old. I just knew I wanted to make something beautiful and I wanted to make something a musician wanted.” Charles learned to play on a fiddle ordered from a Sears and Roebuck catalog himself, before going into the Navy at age 18. His earliest memories of hearing fiddle music was through an old radio the family had in the 1940s.

“The strange thing about making violins, is that you can’t get good at it until you get old. There is some sort of understanding you come upon that you have to live out over many years.”

Red October beans

“While I was in the Navy, I managed to find a book on [making instruments] and I studied it. But mostly when I came out of the Navy in 1955 I built furniture and did cabinetry work. I studied fiddles though every chance I got, and I guess it was 1975 when I committed myself to doing this full time.”

Anne Horner has settled into a chair nearby and prompts Charles to tell me this or that story, and to show me his envelope of family photographs. I turn my camera to her, and she is holding a large open bag of plump pole beans. She snaps them as a kind of physical therapy and tells me she got them early that morning before the heat set in at the farmer’s market. She shows me another bag of red October beans. “Food is the best medicine,” she says. That’s precisely the kind of authentic place where this story is set, a place where the fragrance of garden vegetables fills the room. I’ve come to a place set apart from other places, where solitude is a man building his own set of tools, those he will turn around and use to build a mandolin.

There’s a pause in my questions. His story has been told through the years. But at 83, technique feels less important than the ‘why?’ Seems there’s another story that is pressing at Charles and he begins: “One time in my life, I got to hold and play a Stradivarius. One time.” He pauses and I can tell he is back in that moment holding the benchmark of all craftsmanship, the Stradivarius.

Someone performing in Nashville at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center made the encounter possible for Charles to meet with an instrument made in 1718. “I’ve seen thousands of violins, and I’ve owned and built hundreds of them, but this one just seemed to look at me and say, ‘I’m a Stradivarius.’ Hardly a day goes by that I don’t think about it.”

Charles continues. “You know, Stradivarius did not have an easy life. There was the bubonic plague all around. War. Famine. There was also the thumb of the Catholic priests bearing down, but don’t print that.” He laughs. “It was not a good time. Yet there was Stradivarius working away at making what is still to this day the most beautiful violin in the world. Think about that. A hard life, but somehow he managed to stay with it.”

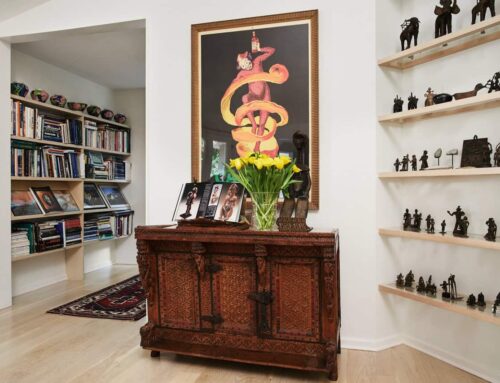

Ready for winter on the mountain

Charles Horner’s life is no romantic Appalachian trope. Though it might be easy to dismiss his world as quaint and even wax envious on a hot August day when the mountain offers enough breeze to turn the whirly gigs he’s made. After all, there’s a rack of carefully stacked wood all around the workshop as poetic as any Robert Frost fetched. The cabin. The snap beans. The curls of wood on the workbench. The scene is nearly intoxicating for a writer who has underlined the works of the Agrarians; but there’s a caution. Reality holds that relentless romantic trope in a balance.

Stradivarius, in the late 1600s worked in a small house at No. 1 Piazza Roma in an attic workshop, a home he rarely left, and a place that might not be much larger than the Horner family’s cabin. The master who must have considered himself somewhat indentured, created more than 1,000 instruments in his lifetime, and around 650 of his violins still survive, get stolen, returned, coveted, displayed, studied, and sometimes played. There’s a hard accounting when you have to put a price on what has helped you survive this life. For the Horners, cancer has been a plague, and they’ve known famine can surface in all sorts of ways as scarcity.

A new violin in production with a fresh coat of varnish. At least ten coats of varnish will be applied over time.

Charles Horner, like the Italian master he holds in awe, has lived a life elevating something beautiful out of life’s amputations, you could say. There’s a hollow inside every life that we can sometimes frame, and that’s where the music can emerge.

There’s a mystery that remains around the work of any luthier. What secrets get shared only through apprenticeship and oral history? Does this or that type of wood affect the sound?

Charles Horner uses what has been available to him, becoming an apprentice to the woodpile, the forest. He certainly knows as much about wood and trees as he does the creative process. He has friends in the lumber business who set aside certain finds for him. His violins are made from maple with spruce tops.

“There’s just a perfection with a violin I admire,” adds Charles. “What other man-made thing can you pick up and enjoy that has not changed significantly in more than 300 years? Any violin is a priceless treasure.”

Some scientists believe a Stradivarius sound doesn’t result from any chemical compound, or egg white glue, or other speculations that have surfaced through the centuries. The superior music may have been a result of wood that was more dense, not because it was somehow superior, but because it had endured a cold winter and a slower growth. From a stunted tree, can come the most expansive musical sound. This ‘Little Ice Age’ history reminds us about what made the maple from the northern forests of Croatia sound a little different for Stradivarius.

Perhaps any seasoned artist gives us master works that reveal a parallel story of the hardships of their life, where both the luthier and his instrument become beautiful in their imperfections. “Stradivarius lived to be 93,” said Charles, “and that was at time when the average life span was probably only 35. He was onto something.”

Photography by Laurie Perry Vaughen

The tuning pegs are made from Brazilian rose wood, no longer available because of conservation protections in place since 1991.

While no two Horner fiddles are alike, these two are twin sisters. And highly impressive.

Patterns of a design that go way back. Think early 16th century.

Wooden inlay of American holly and walnut runs along the curves as delicate as an embroidery stitch, the sign of Horner craftsmanship.

Like a trophy cabinet, each of these violins represent hundreds of hours of construction and care.

For an audience of one, plus the universe. Memorable.

Tennessee’s elder luthier, Charles Gene Horner at his humble Maker Space near Rockwood, TN, enjoys making music

Mandolins with the signature mother-of-pearl inlay of “C Horner” are highly valued

Hand-carved detail of mandolin in progress

Every piece of wood is deemed of carefully stacked and given value, some having traveled long distances to be discovered by the luthier

I was surprised to learn that many of the tools in Charles Horner’s workshop were made by Charles Horner

This scrap may become a chin rest on a fiddle or a tallpiece on a mandolin

Mandolin in progress

A humble Tennessee maker space

The cabin sits across a small pond from the workshop and not far from their modest home. Charles was born in this cabin in 1933, and his father was born there in 1903. Charles has worked to restore the cabin and he also crafted the whirly-gig on the rustic post.

Log cabin exterior wall detail is a map of several generations

What a beautiful article! I am from Australia and bought a fiddle from Charles (Gene) in July 2014. It is an amazing instrument and many people comment on the quality of tone that comes from it. Thank you for such a great piece here!

How did you find one for sale? Who,where etc would help.

Thanks and we share your enthusiasm for his art.