One of Nashville’s most revered artists continues to evolve

By Hollie Deese

Photography by William DeShazer

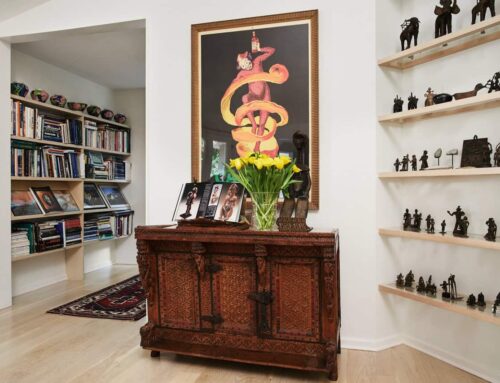

Nashville native Alan LeQuire grew up in a mixed household—as in his mom was a painter andhis father was a scientist. All of their friends were artists and scientists,too, so it made for aninteresting mix for him and his three siblings growing up.

“There were a lot of great arguments,” he says.

Because his mother taught and made art, tools for creating were everywhere. She had a studio and would keep LeQuire and his siblings occupied by giving them projects to work on. He had a natural artistic talent, but the science side pulled LeQuire as well. He studied pre-med at Vanderbilt University, but he says he came to a fork in the road his senior year when he went to France as part of the curriculum for his French minor and decided he was going to pursue art.

“I had apprenticed with several sculptors, and I really felt like I had to get academic training. But it was a mystery because academic training didn’t really exist, so part of the personal quest for me was to find out what remained of it in Europe,” LeQuire says.

He wasn’t impressed with the radical leanings of the French Academy—anti-figurative, anti-tradition—which was considered the gold standard of art education. And the few days he spent at Beaux-Arts de Paris depressed him because it was so far from what he wanted to learn.

“But I managed to find some great teachers over there, so I still got a lot out of being there, justgoing to museums and traveling,” he says. “That sort of formed the basis of solidifying my ideasabout what I wanted to pursue.”

He says his big moment of clarity was meeting Giacomo Manzù in Italy and falling in love with his way of sculpting the female body. “I felt he was doing something completely new and different with that subject matter,” he says.

When he returned from Europe, he went to graduate schoolat the University of North Carolina-Greensboro in North Carolina, where they had a foundry program and a graduate course program based on working from live models—as he did in Italy and France. He continued to draw, make prints, sculpt and cast in bronze.

His first commissions came from his parents’ connections, doing the portrait busts for the medical school at Vanderbilt, then a mother and child bronze commissioned by Mildred Stahlman, a colleague of his father’s at Vanderbilt, for the neonatal wing of the hospital.

“It was a major commission for me at the very beginning of my career,” he says. “They placed it right in front of the window where you looked at the babies, and she had one breast exposed. They got a lot of complaints, and so I think they put it in a closet.”

Next, he created young David playing the lyre for the Blair School of Music. In a very traditional way, LeQuire built a career in the arts based on patronage.

“My career was built by these individual people who responded to something in my work and wanted to support me,” he says. “I’m so thankful for them.”

LeQuire can look back at those early works, though, and see the skill, the influence from Manzù when he was fresh back home from Italy.

“And I kind of wish for that in my work today,” he says.

Birth of Athena

LeQuire’s biggest commission was about to come from another supporter, Anne Roos, who was on the Nashville Park Board. She had spearheaded the fundraising to build a statue of Athena for the Parthenon, and she wanted LeQuire.

The statue was commissioned in 1982, and it challenged the artist in every way. First, he developed a fear of heights while on that project. Even scarier, he was expected to lead a team and have a schedule.

“I didn’t know how to do any of that stuff and was terrible at it,” he says. “I’d never done it before, so I couldn’t really estimate how much time this would take, or that would take. I kind of worked myself into a frenzy early on and with the stress, and I really hurt my back and went to the hospital.”

Those days in the hospital made him realize he had to change his way of working. “I made the decision that I was going to let the project dictate its own schedule and not worry about it. And Anne Roos allowed me to do that.”

Athena was commissioned at the end of 1982 and unveiled in 1990.

In May 2003, he opened his studio on Charlotte Avenue, where he remains today. It was right about the time that he finished Musica, the large-scale naked figures dancing around the Demonbreun roundabout, a monument to signify Nashville’s connection as Music City, and the connection to Music Row.

“I didn’t have any clue that it would be so controversial, but I should have known,” he says.

LeQuire says that today he is “sort of retired” in that he doesn’t have to take commissions anymore, and he is excited about doing stuff that he wants to do. One of those projects has been Dream Forest, which, ironically enough, comes from his early experiences and memories in the Parthenon — and even earlier experiences in the woods near where he grew up.

“I had a series of dreams when I was in my 40s that were me, sort of wandering through an old-growth forest,” he says. “But all the trees were humanoid, sculptural objects with a living presence. I saw the multilayered surface texture, with names and words, and that comes from looking at the Parthenon marbles when I was a kid, because they had graffiti on them — ancient graffiti that the British Museum made sure to include, but they also had contemporary Tennessee graffiti because, in Nashville in the ’60s, kids would still scratch their names in stuff. And that was all in my dream.”

LeQuire says he felt this warmth and welcoming emotional presence from the trees that was like being visited by his ancestors. “I was really excited by it, and I apparently talked about it a little bit too much because my friends were insistent that I had to actually sculpt these things or shut up about it.”

Today LeQuire continues looking at new techniques, and he still wants to make monumental pieces.

“There is a lot happening in the world of sculpture with digital equipment,” he says. “In fact, all the skills that I’ve trained for years to get, you don’t really need anymore.” LeQuire does what he does, however, because it requires the whole body when creating.

“It’s why I didn’t want to paint, because painting just wasn’t physical enough,” he says. “I wanted to be totally involved. And you don’t get that with any machine-assisted sculpting. I resist that because it is antithetical to the experience that I want to have in making art. I want to make some big pieces, but in a way that shows they’re made by hand.”

Show of new works coming

This year for LeQuire will be preparation for his solo show of all new works at the Parthenon in 2025. The show has a lot of meaning for him — not just because of the years he spent in the space sculpting Athena, but also because it will be a showcase for his whole history of sculpture making, the monumentality of which will be amplified by being in the Parthenon. And hopefully, people will get a true sense of the artist beyond his more known traditional works.

“Most of my work at first glance seems traditional, but there’s a really strong emotional current in my work that is about love and kindness. I see it, but I don’t know that anybody else does,” he says.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.