By Hollie Deese

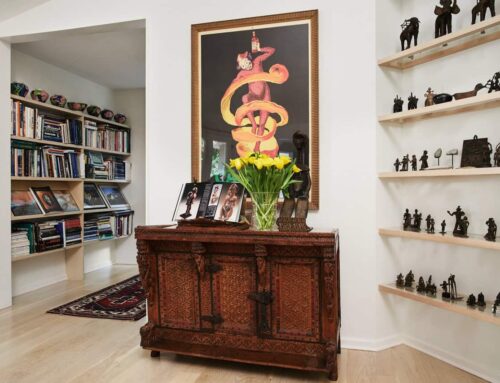

It all starts with a dream. Or maybe it’s more of an inspired vision. But the design for each animal skull Maria D’ Sauza hand-beads appears in her head before she begins to translate it to the piece.

“I always have a book on my nightstand, and I capture everything,” she says. “That’s like my little Bible that goes everywhere with me. I am so amazed each and every time I look at a particular color that’s come into my mind’s eye or through a vision, and I think, ‘How on earth am I going to get this color?’”

Luckily, D’Sauza has bead manufacturers overseas that produce two- and three-dimensional cut beads specifically for her, and they are excited when she pushes them to get the colors she dreams up.

“Usually it’s a yes,” she says.

Building on skulls of the world’s most beautiful animals, D’Souza combines color and dimension to create one-of-a-kind pieces. She says she is inspired by the seemingly random perfection of nature, as she imagines the spirit of the animal and brings it new life through color, motion and depth.

“I was looking at Western art, especially when I was out in Arizona and Wyoming, and I would see a lot of people create on animal skulls. I’m a huge animal lover and wanted to do it ethically, so I found the means and started experimenting with beads and materials, like silver, pewter and copper.”

“I was looking at Western art, especially when I was out in Arizona and Wyoming, and I would see a lot of people create on animal skulls. I’m a huge animal lover and wanted to do it ethically, so I found the means and started experimenting with beads and materials, like silver, pewter and copper.”

Honoring the life of the animal is at the core of D’Souza’s art. Mounts from domesticated Longhorns and bison come from small family farms, animal sanctuaries and parks after they have lived out their lives, often cared for as pets. She does not source from factory farms or meat-processing facilities.

“Some of the pets, I get the stories behind them, and those are really cool,” she says.

As for the mounts of wild animals, they are sourced from a network of people known as “deadhead” and “shed” searchers who scour wilderness for skulls, antlers and horns of animals that have died of natural causes or killed by predators. Animals in colder climates (elk, moose, pronghorn and deer) often die in abnormally heavy and sudden snowfalls, ice storms or severe cold snaps.

Most U.S. states require deadhead searchers to purchase a special salvage tag from their state’s wildlife agency to certify, remove and sell found skulls. The import of mounts from African continents and other foreign nations is also highly regulated, and special licensing is required.

It’s all extra effort she is happy to undertake knowing the regulations generate fees that support wildlife conservation and help prevent poaching. And it’s important to her that people understand that her work comes from a place of honor.

“And just giving it new life, one bead at a time,” she says. “It’s definitely a process where you have to trust. You have to be in the moment — no design is repeated. I’ve tried repeating designs, and I fail every time. So let’s see what the animal calls for.”

D’Sauza has been on many wildlife observatory tours here and overseas, in Africa and in the Middle East. It’s there she fell in love with the Arabian oryx — national animal of Jordan, Oman, Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates — and has built a network of people there to work with.

“In Africa, we actually feed a village when, say, a kudu is hunted. So nothing goes to waste. Everything is used,” she says.

It’s hard for her to say how long each piece takes to complete, especially when they all start in her dreams and visions — if she doesn’t see anything, there’s no work being done. But once she does begin, it can be up to 180 hours for a longhorn or big bison. Recently, a client shipped her an ibex skull from Spain, and it took weeks before the design appeared in her mind’s eye — the pattern, the colors. But once she knew what to do, it was done in about 80 hours.

Always artistic, she painted as a child, her parents joking they couldn’t even fall asleep around her or she would be painting their faces.

“I’ve always painted, always been artistic,” she says. “I think it comes from my grandfather who always painted. He never did much with it, but he always sold locally back in Portugal. So I don’t know whether it’s hereditary or what, but I caught on. I’m very in tune with contemporary art and what you can do with colors.”

Her work is now a part of the permanent collection at the Booth Western Museum in Cartersville, Georgia, as well as the Monthaven Art & Cultural Center in Hendersonville, and she says her ongoing inspiration comes from her exposure to varied cultures — she is Portuguese-Indian and has lived on five continents.

And her ability to give in to the process helps propel her through each project.

“What I realized is that giving up that fear, turning it into blind faith and trusting the process — the steps are totally unknown,” she says. “Clients will ask me if I know what the sketch is going to look like, and I don’t know till it’s finished. I work in the moment.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.