By Robert Jones

Portrait Photography by Anna Haas

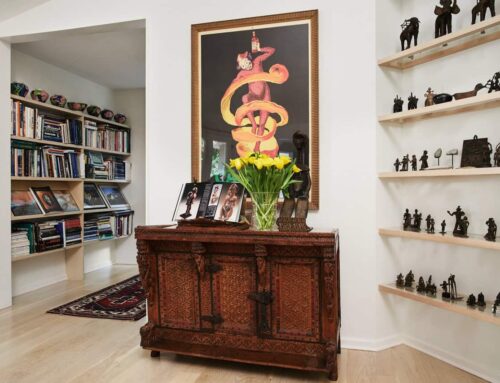

Work Photography by Keavy Murphree

Keavy Murphree’s passion for ceramics has echoed throughout her adult life, resurfacing at pivotal moments of transition. Despite it being her calling, she initially was hesitant to pursue her artistic dream.

“I went to school for industrial design. Even though I’d fallen in love with ceramics, I opted to take the practical route in school. I was raised in the Midwest with these puritanical roots telling me: ‘You might hate it, but work hard and you might be able to enjoy life later.’”

A high school class had originally ignited her interest.

“Then I took a couple classes in college and occasionally pursued it as a hobby. My now husband and I moved to Nashville in 2008, got married, started having kids and it never felt like the right time,” she says.

She overcame her apprehensions when a professional transition gave her a window of opportunity to rethink her career path. She took a class.

“I’d been laid off from my job, and I was doing more freelance work. I thought, Finally, I have time where I can pursue this passion. My goals were just to play with clay all the time. It didn’t extend to anything beyond that.

“But I made this little piece, and a girl in the class was like, ‘Oh my god, i love this, it makes me so happy.’ That was the moment when I saw someone was really responding to it, and it was making her happy. Positively affecting the lives of others was the purpose I had been looking for. I started coming up with several other concepts, and I developed this little family of creatures that was just enough to run with.”

These creatures formed her Horns collection, which she has been making since 2018. Since then, Murphree’s work has received overwhelmingly positive response, becoming highly valued by discerning collectors and recently earning a feature article in LUXE Interiors + Design magazine.

While her seamless transition into a fine arts environment is a testament to her eye for color and composition, Murphree finds herself at the crest of a new wave of fine artists in Nashville who have been taking functional design to new artistic heights.

“Things slowed down during the pandemic, allowing me to better observe the changing seasons and become more attuned to the cyclical nature of life. Things are always changing! This new work is about renewal and growth and acknowledging that all beings are part of a greater ongoing cycle. After a tumultuous couple of years, this botanically inspired work symbolizes a personal mind shift into the vibrancy and vitality that I want to put into the world.”

Hearing her describe the Schumacher Venetian silk velvet she chose to upholster an intricate floral frieze patterned ceramic chair she is working on, it’s hard to know where the line between fine art and design should be drawn.

“I’m working on lighting, more functional objects and considering the possibilities of ceramics for larger wall installations,” she says. “I’m working toward what’s known as collectible design in the art world at large. That’s the world I look to and aspire to more than the fine art world, at least at the moment.”

Keavy Murphree’s work has taken a new direction as she has been reflecting on the divisive political climate during the COVID-19 pandemic—and on her own experiences navigating that.

“I found myself getting excessively mad about politics and things in my personal life. It reached this fever pitch where it was just too toxic to exist in that state, and I needed to choose a different response.”

The introspective nature of her latest work, alongside the scope of its artistic ambition, has attracted attention from the fine arts world. She is preparing for her debut solo show at Julia Martin Gallery in the Wedgewood-Houston arts district scheduled to run through May. It includes a triptych of stylized ceramic faces that she says reflect aspects of her path through the pandemic.

“The first face is called I Don’t Like you Anyway. It’s about having to deal with people I don’t want to be around and finding myself intolerant of them and, in turn, of myself because of how I was reacting.

“The second face is called Let ’er Rip, and it’s about saying things I almost immediately regretted — things that did not need to be said and weren’t constructive to the situation.

“The last one is called Good Grief. It’s about loss and trying to grow and learn from this universal experience. All this sets the stage for my personal mindspace over the past year, where I was just craving something different—something fresh and optimistic but also real.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.