Architects ditch computers and add personal touch with sketches by hand

There is something so special and intimate about a drawing, and when it is of a house you are building from the ground up it can become a part of your family’s documented history.

Kevin Coffey

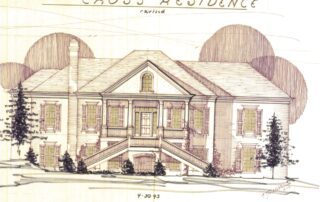

Franklin-based architect Kevin Coffey began drawing houses when he was 7 or 8 years old, and within a few years he had moved on to drawing floor plans, trying to match the elevations on the pamphlets they got when his family moved to St. Louis and was looking for homes.

It was a childhood hobby that could not have been more indicative of his eventual architecture career. But he never really drew outside of sketching homes and really only applied the skill in that context, before choosing architecture as a career, during school and then starting his own firm.

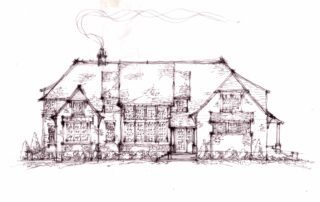

“I didn’t really get the drawing style I have now, which probably started in college,” he says of his relaxed style. “I don’t worry too much about the lines being exactly straight or parallel or anything like that.”

“I didn’t really get the drawing style I have now, which probably started in college,” he says of his relaxed style. “I don’t worry too much about the lines being exactly straight or parallel or anything like that.”

When Coffey was in college, almost everything had to be done by hand — the only computers were the Apple 2s in the lab, and CAD programs were not yet widely used — so sketching and constructing models was the norm.

And he never stopped. Coffey still does a preliminary sketch of just about every project on paper. He keeps the originals, but if the client asks he’ll happily give them copies or do a cleaned-up version for their marketing materials.

Sometimes the original sketch matches the final, sometimes not — it depends on how much the scope of the project changes and if people choose to execute all of the lofty, idealized aspirations Coffey can dream up in a sketch. Either way, pencil and paper can be an accessible way to approach intimidating design elements.

“I think the drawn sketch is not intimidating to a client,” Coffey says. “Most clients don’t respond to a computerized drawing, psychologically, the way they do to a sketch. There’s a romantic edge to the sketch that the 3D models don’t have.”

And Coffey says he rarely spends more than 20 minutes on a drawing.

“They’re about taking an idea and just going with it,” he says. “It’s not like there’s this humongous time investment to get a sketch, but it still communicates a lot of thought. That’s what I’m trying to do with the sketches.”

Joel Tomlin III

When Joel Tomlin III was graduating high school, his father, owner of Landmark Booksellers in Franklin, gave him some sound advice.

“My dad told me, ‘Find something you love to do in life because you’re going to have to work a long time. I believe that my dad and I are tight, and so I was on a mission to try and figure out something that I would like.”

Tomlin had been an outdoors guy his whole life, camping and scouting, but he was also an artist and musician. He started studying outdoor recreation and park planning in Montana, but it didn’t seem like the right fit. He moved back to Nashville and began working for a company that designed and built landscapes. Everything clicked, and Tomlin had found that thing his dad wanted him to.

“I get to be an artist, and I get to design outdoor spaces,” he says. “What’s better than that?”

“I get to be an artist, and I get to design outdoor spaces,” he says. “What’s better than that?”

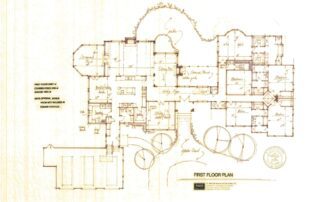

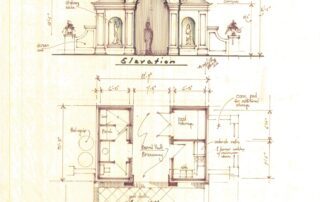

The art comes into play when he is drawing plans. His school had just started to use CAD, but the great architects he studied never had a computer to work on. They just had their drawings.

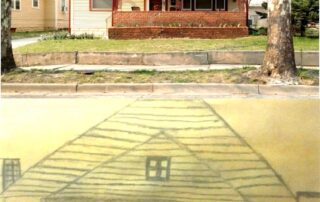

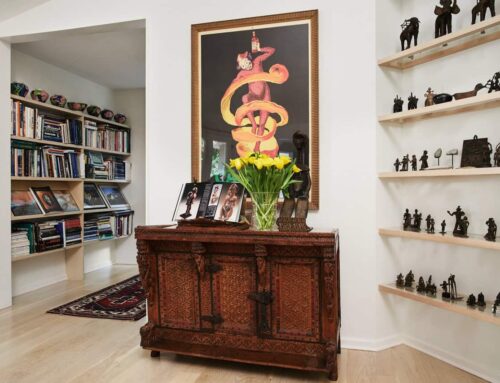

“I love the craftsmanship of design and creating ideas, so it’s not uncommon,” he says of drawing out his plans by hand, working on a drafting board with pencil and pen and different types of papers and color pencils — even watercolors. “Drawing a line takes just as much time whether you do it by hand or whether you do it on a computer. I’m also very visual, so I like to see it all at once. I don’t like scrolling in and out of a screen.”

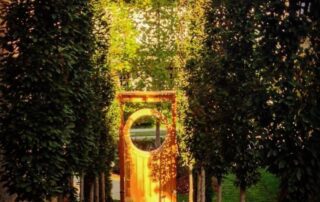

And when he’s finished, the homeowners have a beautiful piece of art to remind them of that place, even if they end up moving.

“I just love the actual drawing, to try to do my best job and make something completely realized on paper into real life,” he says. “And then someone can understand that it’s beautiful in itself before it becomes real. That’s basically me taking that and then seeing the project through from beginning to end.”

Tomlin says there is a good mix of styles in Middle Tennessee, though gardens have historically been pretty traditional. “It’s what they remember when they were young,” he says. “You see a little bit of contemporary, modern stuff here and there. But then you also have a ‘Nashville’ style. It is a city and country in one, a mix of the land and the city being close together, so you have a little bit of a country farm style going here.”

Tomlin recently moved into a new house with his wife, Heather Byrd, and admits they both have plans for how to transform the landscape. But gardens are built over time, and he isn’t in any hurry to rush through something they plan on living with forever. One thing he isn’t touching though, are the 41 decades-old American Boxwoods that line both sides of the semi-circle driveway.

“We inherited something amazing,” he says. “They have been kept in good shape, and they change the whole feel of our house. It’s a technique you used to see a lot on pre-Civil War mansions, and it’s got kind of a historic feel. I’m crazy about them.”

Mitchell Barnett

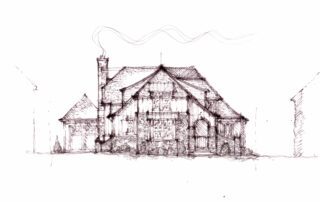

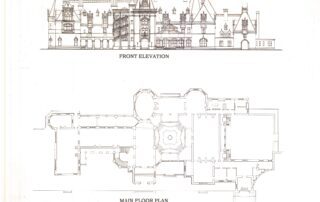

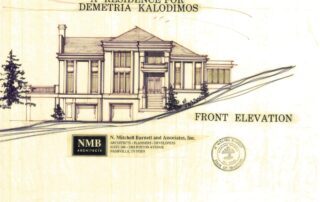

Architect Mitchell Barnett is a native Nashvillian who went to the University of Tennessee-Knoxville architecture school, did an internship, and started his own company 35 years ago — as soon as he got his license. And it was then that he started doing hand-drawn sketches for his projects.

Today, though, the computer is the standard, and he has noticed that fewer and fewer of he graduates he interviews for his firm have any hand-drawing skills.

“They all rely so heavily on the computer, it’s more or less becoming a lost art,” Barnett says. “I would say that maybe even as early as 10 years, maybe 20 years, from now, we’ll probably see very little or very few artistically done, hand-drawn architectural drawings.”

It’s hard not to be sad about the disappearance of a practice that was once standard.

It’s hard not to be sad about the disappearance of a practice that was once standard.

“I think it loses a little sensitivity and a little artistry,” with technology, he says. “But that’s what architecture is. It’s art. It’s our living, sculptural art in the world. When you lose that one little aspect and it becomes so technical … I don’t know, it loses a little bit of the character, a little bit of the emotion and sensitivity, that goes along with it. That just is not something you can do on the computer.”

And it’s a skill that translates to the job site, too, when he can just take out a pen and paper and sketch out his intention for anyone to see. “It’s an immediate connection,” he says.

Barnett took a trip with a group of architects years ago to Cuba. They took one entire afternoon and they left all cameras behind with the goal of just sketching all afternoon.

“We all sketched everything we saw, everything we felt compelled to draw,” he says. “Then at dinner, we presented our drawings in front of the group. It was so much fun. It was so interesting how two people could see the same exact thing and have a different interpretation of it. It was marvelous. It was eye-opening from that perspective, when you realized how important the visuals and the graphics are.”

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.